Very well presented. Every quote was awesome and thanks for sharing the content. Keep sharing and keep motivating others.

Written By Mark E. Jeftovic, Posted on August 20, 2024

August 15th was the anniversary of the infamous “Nixon Shock”, when excessive spending and trade deficits had governments on the ropes, as prices climbed relentlessly, inflation soared into the double digits, while economic growth stalled.

In 1971 of that year, Nixon “temporarily” suspended convertibility of the US dollar for gold (still in effect), while simultaneously proclaiming a 90-day freeze on all wages and prices across the United States.

The stagflationary 70’s also saw Trudeau the 1st enact “The Anti-Inflation Act of 1975”, with his infamous “6 and 5” measures (a 6% cap on wage increases with a 5% cap on prices was supposed to put 1% back into the pocket of the peasants).

None of this worked, and as the lumpenpublic were mulched by higher prices and growing government, gold served as a barometer to it all – soaring from $35/oz at the time of the Nixon Shock to $850/oz in 1980 (that all-time high still won’t be exceeded in inflation adjusted terms until gold cracks about $2,580).

It took Paul Volcker to get inflation under control with double-digit interest rates – (when the news came that he had been elevated from President of the New York Fed under Gerald Ford to Chairman by Jimmy Carter, Volcker’s wife burst into tears).

Today, 50 years later with a monetary regime that makes the 70’s look austere, double-digit interest rates are simply not an option – we’ve just seen a 5-sigma event nearly blow up the global monetary system from the BoJ nudging interest rates from the zero bound to 25bps.

With an unprecedented levels of monetary expansion and debt levels somewhere beyond nosebleed elevations, policy-makers and central bankers are trapped.

This is why we’re seeing a resurgence in popular rhetoric around the idea of price controls – everywhere from Jagmeet Singh here in Canada, who blames grocery store CEOs for inflation, to Dem nominee and incumbent Vice President Kamala Harris, channeling him with promises of food price controls as part of her election campaign.

The definitive chronicle of price controls throughout recorded history comes to us by way of Robert L. Schuettinger and Eammon F. Butler’s “Forty Centuries of Wage and Price Controls” – or “How Not to Fight Inflation“.

I could not for the life of me find my hard copy, but during the depths of the Global Financial Crisis, The Mises Institute saw the value in republishing it…

“By special arrangement with the authors, the Mises Institute is thrilled to bring back this popular guide to ridiculous economic policy from the ancient world to modern times. This outstanding history illustrates the utter futility of fighting the market process through legislation. It always uses despotic measures to yield socially catastrophic results.”

It starts as far back as Urakagina of Lagash, a King of Sumeria in around 2350BC who came to power and overturned wage and price controls held in place by an unnamed line of despotic predecessors:

“[he]began his rule by ending the burdens of excessive government regulations over the economy, including controls on wages and prices…

An historian of this period tells us that from Urakagina,‘we have one of the most precious and revealing documents in the history of man and his perennial and unrelenting struggle for freedom from tyranny and oppression.’

This document records a sweeping reform of a whole series of prevalent abuses, most of which could be traced to a ubiquitous and obnoxious bureaucracy …it is in this document that we find the word ‘freedom’ used for the first time in man’s recorded history; the word is ‘amargi’.“

It is somewhat telling to find that the word “freedom” was seemingly coined to describe the end of price controls.

The Code of Hammurabi of ancient Babylon is often cited as one of the earliest legal codes, thought to be the first to enshrine the presumption of innocence, but it also contained detailed tables of price controls on everything from goods to services – like the hiring of a wagon (“forty qa of corn per diem”) to the wages of a field laborer (“eight gur of corn per annum”).

According to Schuettinger and Butler, historical records show that Hammurabi’s price controls dampened trade and economic activity for both Hammurabi and his successors, citing W. F Leemans, who found that:

Prominent and wealthy tamkaru (merchants) were no longer found in Hammurabi’s reign. Moreover, only a few tamkaru are known from Hammurabi’s time and afterwards . . . all . . . evidently minor tradesmen and money-lenders.

Concluding:

“it appears that the very people who were supposed to benefit from the Hammurabi wage and price restrictions were driven out of the market by those and other statutes.”

Finding that:

“There was a remarkable change in the fortunes of the people of Nippur and Isin and the other ancient towns which he ruled, which came in the middle of Rim-Sin’s reign [Hammurbi’s predecessor – whose policies he extended] . The beginning of the economic decline corresponds exactly with a series of “reforms” inaugurated by him.

For the first of many times throughout this piece, I will ask the reader to “hold that thought”.

We can fast forward to ancient Greece where Athens, a city state “perpetually short on grain” sought to control the prices at which it was sold in order to keep them “just”. At one point, under a measure that was supposed to be temporary (sound familiar?), state appointed corn buyers called “Sitonai” were mobilized to set the pricing.

Predictably, the problem got worse, and there were calls to make the measures permanent. One politician, Lysian of Athens wanted to put grain dealers who broke the code to death.

The book is exhaustive in its examinations, covering China, India, the Medieval age, even modern times (Canada and the US in the seventies) – but ancient Rome warrants a deeper look – particularly the road to Emperor Diocletian’s Edict of 301AD.

“Under the tribune Caius Gracchus the Lex Sempronia Frumentaria was adopted which allowed every Roman citizen the right to buy a certain amount of wheat at an official price much lower than the market price.

In 58 B.C. this law was “improved” to allow every citizen free wheat. The result, of course, came as a surprise to the government.

Most of the farmers remaining in the countryside simply left to live in Rome without working.

If that wasn’t enough:

Slaves were freed by their masters so that they, as Roman citizens, could be supported by the state.

(There is a modern day analog here with open borders and the illegal immigration crisis – where we could be looking at mass migrations as being, at least partially, incentivized by governments of weakening economies trying to jettison dependents and potential rebels – offloading them to countries dumb enough to think they’re acting enlightened by taking them on and supporting them).

By 45BC, Julius Caesar found that roughly a third of the citizenry was living on “free food” from the government.

He managed to reduce this number by about half, but it soon rose again; throughout the centuries of the empire Rome was to be perpetually plagued with this problem of artificially low prices for grain, which caused economic dislocations of all sorts.

Succeeding emperors resorted to the ancient version of “Quantitative Easing” – currency debasement:

In order to attempt to deal with their increasing economic problems, the emperors gradually began to devalue the currency. Nero (A.D. 54–68) began with small devaluations and matters became worse under Marcus Aurelius (A.D. 161–80) when the weights of coins were reduced. “These manipulations were the probable cause of a rise in prices,” according to Levy. The Emperor Commodus (A.D.)

By Diocletian’s time in the 4th century it reached truly hyper-inflationary levels when measured in other provincial currencies:

Egypt was the province of the Empire most affected, but her experience was reflected in lesser degrees throughout the Roman world. During the fourth century, the value of the gold solidus changed from 4,000 to 180 million Egyptian drachmai.

Gresham’s Law states that “bad money drives out the good” – it means that rapidly devaluing or debased currencies are traded for anything other than themselves (which drives prices denominated in that currency up) – while “sound” currencies, like gold, or nowadays Bitcoin are hoarded – or at least more carefully spent.

“[I]n the years before Diocletian, emperors were issuing tin-plated copper coins which were still called by the name ‘denarius.’ Gresham’s Law, of course, became operative; silver and gold coins were naturally hoarded and were no longer found in circulation.”

The result of iterative generations of government mismanagement and currency debasement was the hollowing out of the middle class:

“The middle class was almost obliterated and the proletariat was quickly sinking to the level of serfdom. Intellectually the world had fallen into an apathy from which nothing would rouse it.”

The same thing is happening today, but in Diocletian’s time, he saw what was happening and moved to impose some kind of order, first by issuing a new Denarious, that after centuries of declining silver content, openly contained none:

…and then, moving to a system that attempted to replace money entirely (again, hold that thought):

Since money was completely worthless, he devised a system of taxes based on payments in kind. This system had the effect, via the ascripti glebae [tenant serfs], of totally destroying the freedom of the lower classes—they became serfs and were bound to the soil to ensure that the taxes would be forthcoming.

But he had a dilemma:

The principal reason for the official overvaluation of the currency, of course, was to provide the wherewithal to support the large army and massive bureaucracy—the equivalent of modern government.

Diocletian’s choices were to continue to mint the increasingly worthless denarius or to cut “government expenditures” and thereby reduce the requirement for minting them.

In modern terminology, he could either continue to “inflate” or he could begin the process of “deflating” the economy.

Diocletian decided that deflation, reducing the costs of civil and military government, was impossible. On the other hand: To inflate would be equally disastrous in the long run.

Diocletian’s problem is the same one central banks and policy makers face today, all over the world:

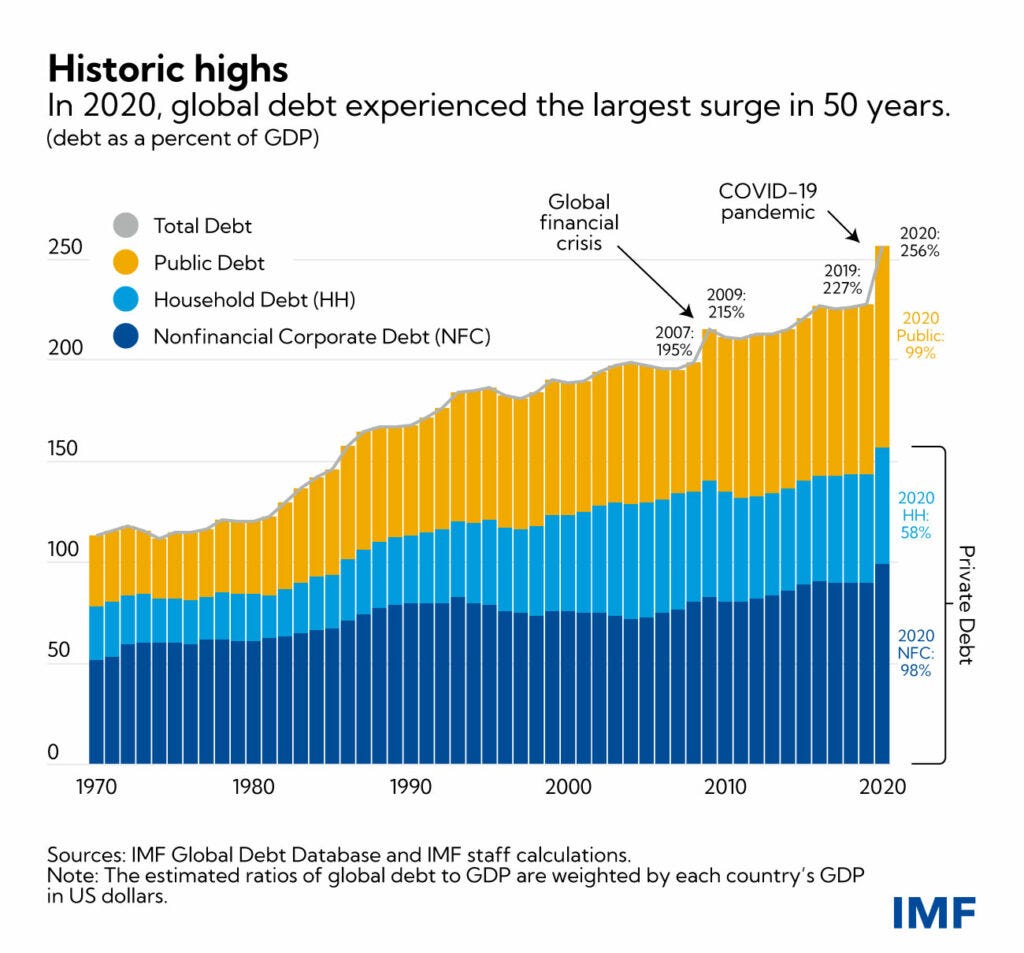

The world is awash in too much debt – with debt-to-GDP more than doubling from 100% to over 256% since the Nixon Shock. With interest rates being artificially suppressed for decades – austerity is off the table, for now — I’ve been writing for years how CBDCs and #Netzero are essentially setting the table for forced austerity.

But we’re not there yet – retail CBDCs are a few years away from being ready but the global financial system is unravelling now (in the meantime, you can get on the waiting list for my CBDC Survival Guide, which is coming out this fall).

How did Diocletian navigate the quagmire?

As Schuettinger and Butler recount,

It was in this seemingly desperate circumstance that Diocletian determined to continue to inflate, but to do so in a way that would, he thought, prevent the inflation from occurring.

He sought to do this by simultaneously fixing the prices of goods and services and suspending the freedom of people to decide what the official currency was worth.

Contrary to our own political leaders, Diocletian wasn’t stupid (in fact, he may have been the most intelligent Roman Emperor after a long string of weak minded half-wits who were propped up by the military).

He knew that the incentives would be against the productive class working, selling, and entrenpreneuring at a loss and he understood that Incentives Are Everything. In his case:

“if farmers, merchants and craftsmen could not expect to receive what they considered to be a fair price for their goods they would not put them on the market at all, but would await a change in the law (or in the dynasty).”

So Diocletian had to realign people’s incentives:

“From such guilt also he too shall not be considered free, who, having goods necessary for food or usage, shall after this regulation have thought that they might be withdrawn from the market; since the penalty ought to be even heavier for him who causes need than for him who makes use of it contrary to the statutes.”

The penalty was …death.

Same for anyone who purchased goods or services at prices above the prescribed amount (no matter how hungry or desperately you needed something or how scarce that something was).

As draconian as that sounds, it almost looks like more people were killed by deprivation and mob rule than were executed for violating price controls:

There was much blood shed upon very slight and trifling accounts; and the people brought provisions no more to markets, since they could not get a reasonable price for them and this increased the dearth so much, that at last after many had died by it”

The authors go on to cite Roland Kent:

“In other words, the price limits set in the Edict were not observed by the traders, in spite of the death penalty provided in the statute for its violation; would-be purchasers, finding that the prices were above the legal limit, formed mobs and wrecked the offending traders’ establishments, incidentally killing the traders, though the goods were after all of but trifling value; hoarded their goods against the day when the restrictions should be removed, and the resulting scarcity of wares actually offered for sale caused an even greater increase in prices, so that what trading went on was at illegal prices, and therefore performed clandestinely.

Within four years, the law was set aside, and Diocletian abdicated.

Michael Rostovtzeff, another leading Roman historian, remarked:

“Diocletian shared the pernicious belief of the ancient world in the omnipotence of the state, a belief which many modern theorists continue to share with him and with it.”

Since the unprecedented monetary stimulus during Covid, we are now beginning to see exactly how trapped we are – with politicians taking victory laps for 2.9% inflation (hedonically adjusted and perpetually revised) – nobody is really remarking that the official targeted inflation rate is in the process of being hiked by half from 2% to 3% target.

The Fed is getting ready to cut interest rates, the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England and the ECB are already cutting and as I told readers in the latest issue of The Bitcoin Capitalist, the Bank of Japan just showed the world that they can’t raise:

On Tuesday, August 6th, the Bank of Japan and the Ministry of Finance held an emergency meeting, and the next day announced “no more rate hikes” until the global financial system could handle it.

Which will be never.

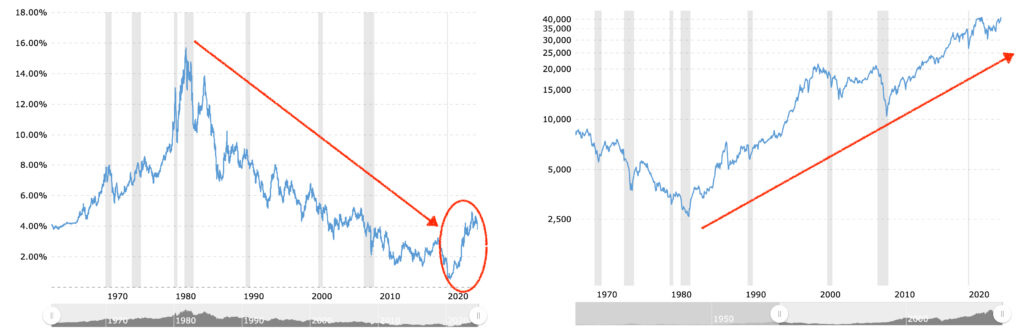

For the first 50 years of the post-Bretton Woods era, since the Nixon Shock, monetary debasement has been mostly under-the-radar and after the stagflationary 70’s, had been largely confined to asset inflation.

This was thanks to a massive bond super-cycle that saw the cost-of-capital come down for 50 years, igniting an asset bubble on the other side of the ledger:

Consumer inflation never really started hitting hard until the aftermath of Covid, and the central banks took to hiking rates to try and get it back under control (my suspicion was always that what they really wanted to do was reload as high as possible so they could cut, once again):

Again, from this month’s TBC (see end of this post for a trial deal):

We’ve been saying since the Fed originally started hiking, that they would do so until something broke.

In March of 2023, something broke – with Silicon Valley Bank and the regional banking crisis; it was quickly papered over with FDIC backstops on all deposits, while the Fed abandoned their balance sheet reductions and quickly reinflated the money supply.

Everything since then has been a theatrical, slow-motion pivot.

Now, after this Bank of Japan miscalculation, something really broke – and the world now sees how the BoJ is trapped, the rest of the central banks are paused or already cutting, right when the global liquidity cycle is starting to turn back up.

(Also – M2 is also beginning to rise again)

All the usual tricks which got us this far, money printing, interest rate suppression, ballooning debt have finally run out of runway because they are now resulting in. consumer price inflation.

This is 100% the fault of bad political leadership and central bank policy but that will never be admitted (to be fair, the St. Louis Fed’s Chris Neely authored a piece in 2022 explaining “Why Price Controls Should Stay In the History Books“)

Instead, politicians will resort ad hominem attacks on the productive class, and absurd accusations that it is the fault of investors and entrepreneurs, who must navigate the risks of monetary debasement, for causing it.

Hence, we have Kamala Harris seemingly anchoring her political campaign on “ending price gouging” once she’s in office.

She seems to be channeling Canada’s own champagne socialist, Jagmeet Singh, the Rolex wearing, Versace sporting millionaire who routinely demonizes CEOs – particularly those of grocery store chains, for causing inflation:

Corporate greed in our country has reached a breaking point after decades of Liberal and Conservative governments that have rewritten the rules to favour the ultra-rich.

Now, every bill you pay makes CEOs richer.

It’s wrong.

I’ll change the rules to help you, not CEO profits.

(What’s ironic in both cases, is Harris is promising to do something upon being elected, although she’s the incumbent Vice President since 2020, while Jagmeet Singh is the one person in Canada, who is single-handedly propping the Trudeau government in power with a coalition government that he could end at any time).

After one looks at the historical record – 4,000 years of endless failures, in price controls, communism and every permutation of centrally planned economies, there has to be a reason politicians are still reaching for it as a solution to problems they have caused and why a small – but vocal and influential, segment of the public cheerleads this as a net benefit for society.

The secret sauce of “it’s different this time” is technology – particularly Big Tech, big platforms, Total Information Awareness and surveillance. Central planners think it is now technically feasible to run all the calculations and tracking in real time that would enable unrestrained monetary stimulus while keeping a lid on negative externalities like inflation.

Politicians like Kamala Harris and Jagmeet Singh are just farming public sentiment created by their own policy failures, but there are very serious people – mostly unelected technocrats of a particular globalist mindset, who think we have the means, motive and opportunity to create a kind of “fully automated luxury communism”.

One of my go-to clips for illustrating the mindset is J Michael Evans at a WEF meeting talking about coming personal carbon trackers:

I’ll lay out the quote again here:

“We are developing, through technology, an ability for consumers to measure their own carbon footprint. What does that mean? That’s where are they travelling, how are they traveling? What are they eating? What are they consuming on the platform? So, individual – carbon – footprint – tracker. Stay tuned, we don’t have it operational yet, but it’s something we’re working on”.

The stage is set, when politicians tell you they want to be able to control prices, believe them – but what the public must understand is that price controls means spending controls.

The politicians will tell you that it’s all about putting “greedy CEOs” in their place.

What they won’t tell you is that price controls also means is telling you what you can or cannot eat, how you use energy – whether you’ll be permitted to travel, or make any other kind of economic decision or make any kind of value exchange that you used to take for granted.

In a world of price controls, that’s over.

Throughout history, price controls have always brought about serfdom and tyranny because that is the only way to override individual incentives. In today’s highly wired world that would mean total technocratic feudalism.

The most vivid example we have today is Venezuela – where price controls were so effective, the rabble had to break into public zoos to eat the animals.

Sign up for the Bombthrower Mailing List and get The CBDC Survival Guide when it drops this fall (you’ll also get a copy of The Crypto Capitalist Manifesto while you wait).

Follow me on Twitter, or Nostr. You should also try The Bitcoin Capitalist for one month here

Mark E. Jeftovic is the CEO of easyDNS and the publisher of Bombthrower Media. Former candidate for the federal Libertarian Party.

[…] Authored by Mark Jeftovic via TheNationalTelegraph.com, […]