Written By Andrew Mahon, Posted on June 1, 2020

A publicly funded health care system, free at the point of use, is one of the many things that Canada and the United Kingdom have in common. Both of these universal health care systems are lauded as sources of national pride, both cost a fortune, and both are often used as political weapons, usually deployed against conservative politicians.

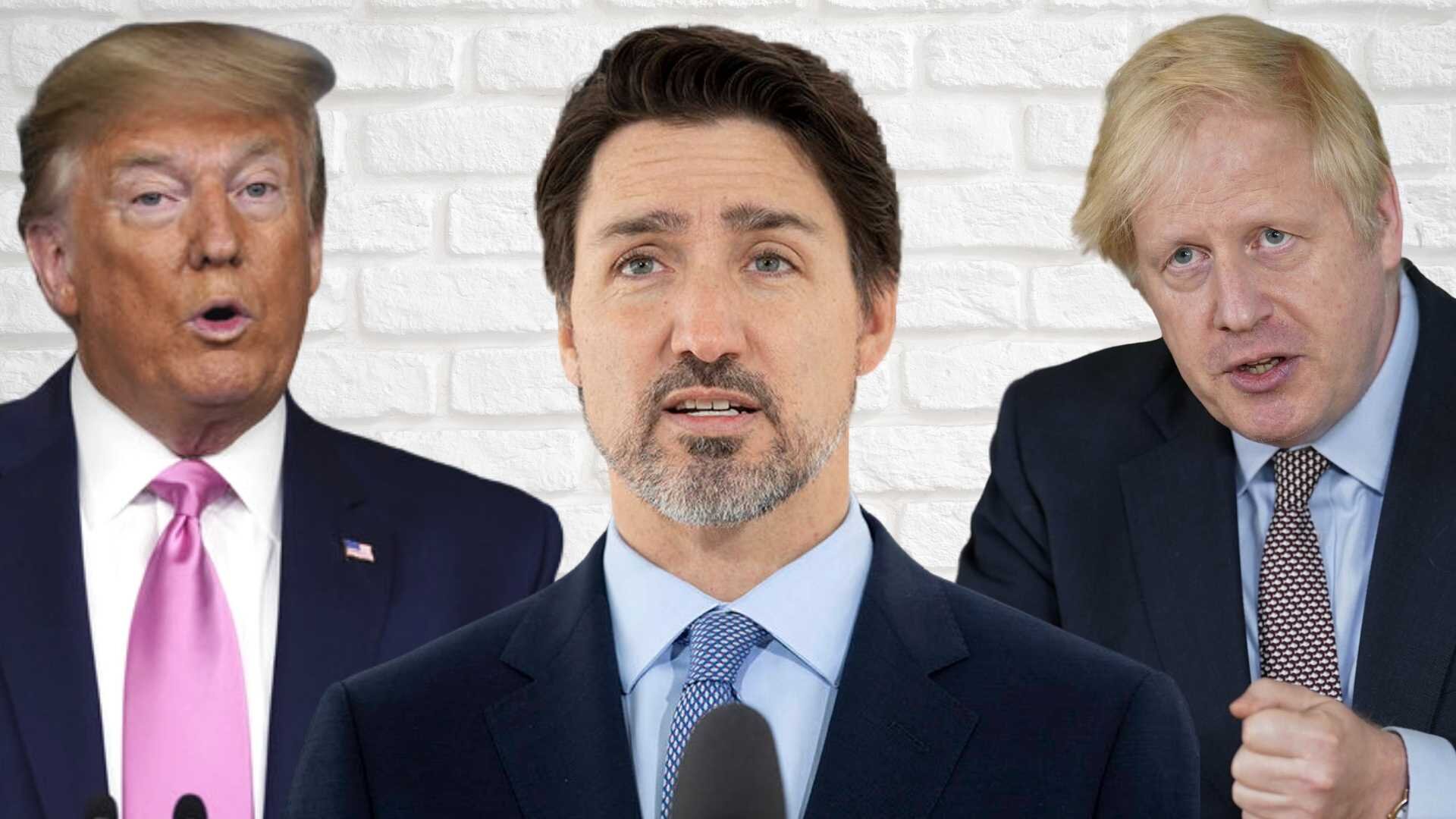

Britain’s Conservatives have often been accused of being anti-NHS (National Health Service). Notwithstanding last year’s bizarre warnings of an NHS selloff to Donald Trump, there’s little to no truth to the accusation — all political parties in the UK support the NHS almost unreservedly. But the coronavirus pandemic has provided Boris Johnson’s Conservative government with an opportunity not just to bury this undesirable image once and for all, but to claim for the Conservatives a new reputation as the party of the NHS.

After the pictures of overwhelmed Italian hospitals scared Western governments to the point of panic, the British threw everything they could at preventing a similar outcome in the UK. The slogan for one of the West’s most repressive lockdowns was “Stay home. Protect the NHS. Save Lives.” One of Britain’s greatest living historians, David Starkey, explained in a recent interview that the singular concern of the government became to “protect the NHS at all costs,” which led it to “stop all forms of surgery and diagnostic testing completely — cancer, heart disease, the lot. The National Health Service becomes the National Covid Service.”

One strategy employed to protect the NHS was to empty out the hospitals in anticipation of a wave of new coronavirus patients. On March 19, the government issued a guidance document entitled COVID-19 Hospital Discharge Service Requirements, in which it urged that “unless required to be in hospital…patients must not remain in an NHS bed…acute and community hospitals must discharge all patients as soon as they are clinically safe to do so.” The aim was “to free up at least 15,000 beds by Friday 27th March 2020.” Care home providers were directed to “identify vacancies that can be used for hospital discharge purposes”.

The upshot of this was that elderly patients in hospitals returned to care homes, bringing with them, in many cases, asymptomatic or presymptomatic coronavirus infections. “Why were we so casual about care homes?” Starkey asks rhetorically, “Because they’re not part of the NHS.” Care homes were outside the scope of the “save the NHS” plan. So in a catastrophic error, the government ordered that the most vulnerable be moved from hospitals — known to be nosocomial virus cesspools — to care homes, the very places with the highest concentration of other vulnerable people.

As the Globe and Mail reported on 20 May, the same scenario has unfolded in Canada: “Though well intentioned, the shoring up of hospitals came at the expense of seniors’ homes, which received far less attention before the virus took off in Canada….During the month of March, Quebec hospitals were directed to do ‘load shedding,’ freeing beds by postponing elective procedures and transferring patients.” Some local health authorities paid care homes to take patients from hospitals. In Ontario, according to the Globe, hospitals sent 1,589 patients to long-term care homes and 605 to retirement homes.

Provincial governments ought to be held accountable for this disastrous course of action, but the federal government must share the blame. In a guidance document issued by the government of Canada — COVID-19 pandemic guidance for the health care sector — the following recommendations are made: “reduce or cancel elective admissions and surgery to maximize medical and critical care bed capacity…discharge as many patients as possible based on revised criteria for discharge”. And further down, in a section entitled Risk Management Approach: “cancel or delay elective admissions and surgery, and other services that can be postponed…Consider earlier patient discharges with community supports”. Clearing out the hospitals in order to protect the healthcare system was a national strategy. The Liberals, after all, like to be seen as the party of public health care.

In Italy the vulnerable are more integrated with the healthy within the general population because the elderly tend to live with their younger families. As the coronavirus spread through the younger population, the unprotected elderly increasingly required hospitalization. In countries that put their elderly into care homes, however, the same pattern wasn’t likely to be replicated. The obvious solution would have been to put measures in place to protect those vulnerable people whom we’ve already segregated from the young and healthy. But the British and Canadian governments wanted to save the hospitals, not so much the people, because if the public healthcare system proved unable to cope, the blame would fall on the governments. The results of this political calculation have been horrific.

As of the 20th of May, according to UK Health Secretary Matt Hancock, “27% of coronavirus deaths in England have taken place in care homes”. This is lower than the European average of closer to 50%, which is allowing the care home scandal to be downplayed in the UK for the time being. But it translates to nearly 10,000 deaths. In Canada, according to Chief Public Health Officer Theresa Tam, an almost unbelievable 81% of coronavirus deaths are “linked to long term care facilities”.

The figure is so staggering that no response is adequate. So they sent in the army — which has brought to light horribly unsanitary conditions in nursing homes and has prompted Ontario Premier Doug Ford to launch a full investigation, leaving “no stone unturned”. But will that include an investigation into this “load shedding” strategy? “I don’t think this government failed seniors,” Ford proclaimed, but added, “I take ownership, I take full ownership.” But this scandal goes beyond the provincial governments, so he and the other premiers ought to share that ownership with Federal Minister of Health Patty Hajdu and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

Covid-19 is not a very serious disease for the vast majority of the public. It is ugly and potentially fatal to the elderly and to those with underlying health conditions. But if you’re under 65 you’re more likely to die in a car accident. Outside of long-term care facilities, fewer than 1500 Covid-19-related deaths have occurred in Canada. Every single one is lamentable, but that number should be put into perspective: every month more than 20,000 Canadians die from all causes; annually there are approximately 15,000 alcohol-related deaths in Canada (and alcohol sales have increased during lockdown); there are 6000 annual deaths from influenza and pneumonia; 50,000 from heart disease; 80,000 from cancer; and, to lead all causes of death (for those who consider them to be deaths), 100,000 abortions.

It may be hard for people to admit once they’ve acquiesced to the fear mongering, but the evidence is growing daily that the world has massively overreacted. Governments panicked and responded prematurely with grossly disproportionate measures aimed at those who are not at risk. The young and healthy have been confined to their homes; the elderly and vulnerable were led like lambs to the slaughter. Meanwhile, the economy has been shut down, unemployment has risen, domestic abuse has increased, suicides have increased, cardiology and cancer patients are not receiving treatment, which will lead to many deaths, and it is projected that millions could starve in poorer countries. All side effects of lockdown.

But the decision to empty hospitals and fill up the nursing homes wasn’t a side effect of anything. It was a deliberate strategy. If it hadn’t been taken, it’s a reasonable assumption that a significant number of elderly people would still be alive. In their hysteria and fear, our governments did something that directly spread the virus to those most at risk and has led to many unnecessary deaths, in the name of protecting the public. It’s a tragedy, and the question that needs to be asked is, were our governments looking out for the public or for themselves?

Very well presented. Every quote was awesome and thanks for sharing the content. Keep sharing and keep motivating others.