Very well presented. Every quote was awesome and thanks for sharing the content. Keep sharing and keep motivating others.

Written By Anthony Daoud, Posted on May 6, 2020

Conservatism in the anglosphere is at a crossroads.

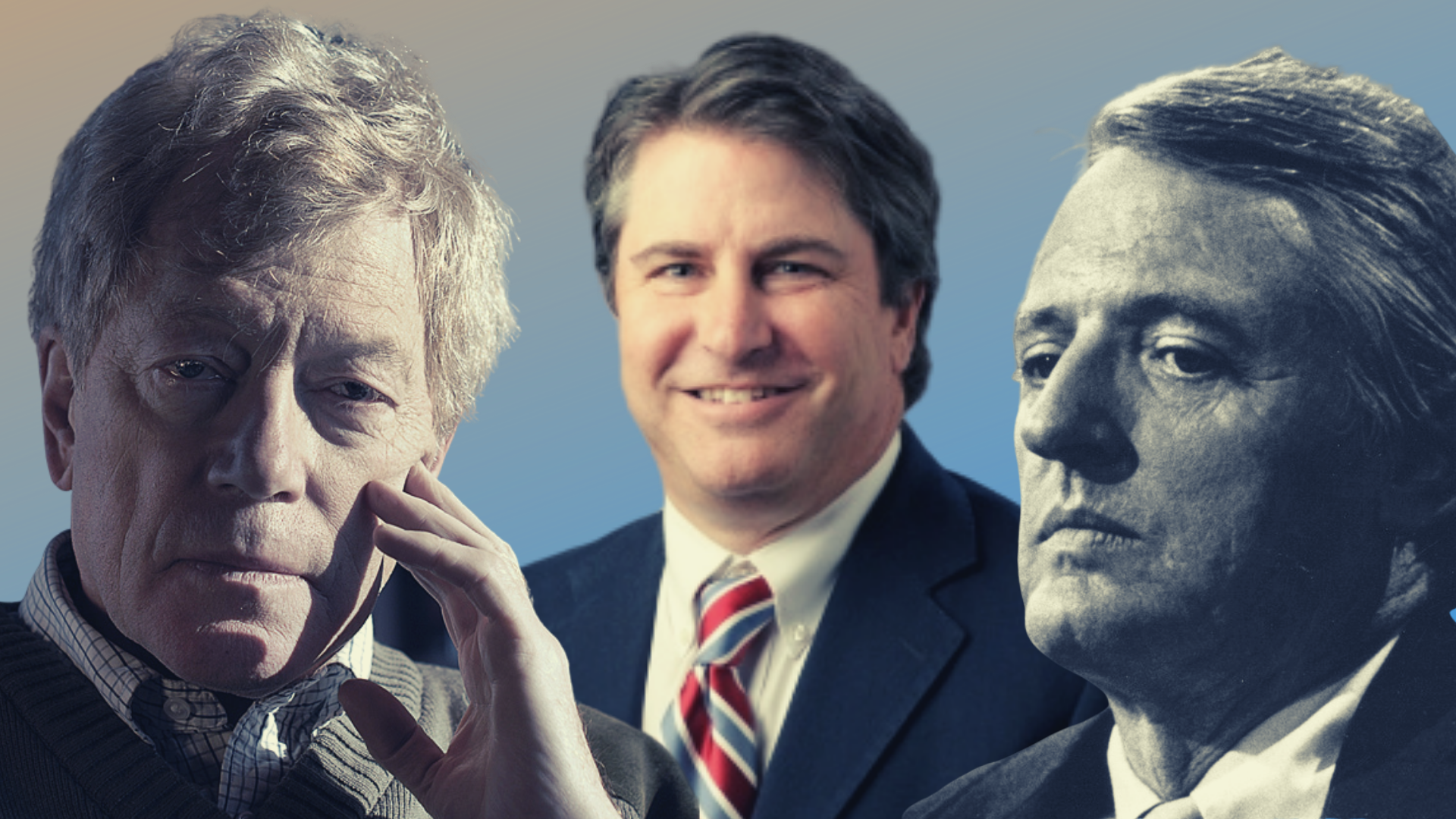

To rekindle the Great Tradition, conservatism must centre its focus on a common good core in social order and the family unit. In recent years, Sohrab Ahmari, Harvard professor Adrian Vermeule, and political theorist Patrick Deneen’s intellectual coalition is actively challenging libertine hegemony over conservative politics. The alternative they propose is not foreign to conservatism but congruent to its intellectual tradition.

William F. Buckley’s once monopolizing fusionism is swiftly uknotting and entrenching cavernous divisions amongst factions. Originally, Buckley’s advocacy for unification between traditionalists and libertarians functioned because the West faced an immediate threat in the Soviet Union and her numerous agents. Rather than dallying through theory to achieve unanimity amongst conservatives, Buckley sought to rapidly coalesce factions as a means of efficaciously repudiating leftist threats. His endeavour was made possible through The National Review, the first austensibly conservative publication in the United States.

The novel fusionist ideology distilled conservatism and simplified its core philosophy to an irrational aversion towards government and a steadfast allegiance to market liberalism.Their philosophies centralized around the tenets of minimal government and “market-liberalism”, that diametrically opposed the Marxist state.

When the Berlin Wall the Soviet Union formally collapsed, a euphoric optimism disseminated throughout the West. Liberty triumphed over tyranny. This event provoked political theorist Francis Fukuyama to pen his magnum opus, the End of History. His work describes the triumphs of liberty and boastfully predicted the proliferation of democratic regimes. According to Fukuyama, the world was on the verge of unforeseen prosperity. Reading Samuel Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations and Patrick Buchanan’s The Death of the West provides a more sobering account of the Western world’s current erosion. Unlike Fukuyama’s optimistic account, we are marching towards imminent chaos while our representatives have neglected the calls for realigning our course.

The previously harmonious marriage between libertarians, moderates, and traditional conservatives is disintegrating. Only the unapologetically common-good camp can salvage the Great Tradition from vanquishing. To do so, the foremost duty is to reorient conservative thought to the good via social order and the family.

While one can trace conservative thought to Aristo-Thomism, modern conservatism originated as a reaction against the French Revolution and its destructive ethos. The Revolution was described as the vanguard movement for modern republicanism and effectively axiomatized an egalitarian framework disguised as Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité. The cultural horrors the revolution produced, and Maximilien Robespierre’s sanguine reign typified the abhorrent nature overthrowing order caused in France. In many ways, the French Revolution mimicked the fall of man in John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Just as Adam and Eve were tempted by the serpent, the French Jacobins turned public sentiment against the social order defended by Monarchy and the clergy. The Jacobin ésprit replaced God with a deified reason and placed man as the universe’s primal agents. In the Revolution’s sanguine ensuing years, man’s libido dominandi was displayed; hundreds of thousands were murdered and the clergy were subject to egregious treatment. Severing from her heritage as the Catholicism’s eldest daughter, France was orphaned by a libertine worldview.

Edmund Burke’s tendentious polemic, Reflections on the Revolution in France, effectively enshrined him as the “father” of conservatism. Being an Irish Anglican Whig politician, he was immersed in a Roman Catholic environment but felt deeply connected to Britain. His Reflections warned against Britain pit-falling into Jacobinism by proposing a rigorous defence of ordered liberty under natural law’s auspices. Structuring social order in accordance with Natural Law provides denizens with a series of rights apropos life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness (private property). These requisites enable the cultivation of good virtues oriented towards attaining a transcendent end. Law, for Burke, had a telos that befitted reality (nature), and as Josef Pieper eschews in The Four Cardinal Virtues, all acts concurrent with reality created by God, are good. Should society be stripped from the order keeping it intact, vice would permeate “without tuition and restraint”.

A controversial paragon of conservatism, Joseph de Maistre was perhaps the most notorious French counter-revolutionary thinker. Akin to Burke, he subscribed to the concept of ordered liberty in his political bodies of work insofar as arguing in favour for the divine source of political legitimacy intimately linked to the natural law. University of Manitoba professor, Dr. Lebrun, elucidates that while Maistre makes faint allusions to the natural law in his political thought, he concedes it animates the adjudication of a legislator and is “the ultimate sanction for civil law”. It also engenders political order designed to “build high and build for centuries” as he describes in The Generative Principle of Political Constitutions. In the absence of natural law, where sovereignty is exclusively dictated by the ever-fluctuating popular will, virtue, the predicate for “temporal happiness”, wanes.

Burke and Maistre’s ideas on Natural Law were derived from St. Thomas Aquinas, who reconciled Aristotelian ethics with Christian thought. He was a vanguard in introducing classical philosophy into the High Middle Ages and cited numerous Greco-Roman figures in his Summa Theologia. To this day, Aquinas’ Summa remains unparalleled as the greatest philosophical work in the Western tradition, covering a slew of topics ranging from theology to politics. Virtue, for Aquinas, not only led to eudemonia but additionally allowed man to reach a metaphysical telos — a final end.

Importantly, attaining one’s end was not an individualist endeavor. Dissimilar from the Lockean-Hobbesian individualism our culture proscribes, Aristo-Thomism understands polity as a cohesive unit communally oriented towards the good. Hence in Question 90 on the Essence of the Law, Aquinas advances “A law, properly speaking, regards first and foremost the order to the common good” (ST). Citing Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics, Aquinas forbye concludes; “A private person cannot lead another to virtue efficaciously: for he can only advise, and if his advice be not taken, it has no coercive power, such as the law should have, in order to prove an efficacious inducement to virtue” (ST).

Although Thomas concedes law should refrain from sanctioning all vices, respect for the Natural Law is given primacy and the polity’s structure ought to be geared towards the common good. Edmund Burke’s ordered liberty reiterates the Aristo-Thomist position on the Natural Law as a concomitant to the common good.

Common-good conservatism found an ally in Sir Roger Scruton, who’s rich political thought was deeply inspired by Burke’s philosophy. Committed to preserving place and community, Scruton ambitiously fought against the oikophobia fostering nihilism and historical rectification in the West. Communities, for Scruton, were sacred insofar as they bequeathed knowledge, trust, and organically gave rise to institutions. In a 2013 Guardian article, Scruton typified Burke’s position in an urge to reclaim authentic conservatism. On liberty, he succinctly expressed “but no freedom is absolute, and all must be qualified for the common good. Regarding law, Scruton opposes the liberal narrative that they are merely contractual and subject to change viz à viz vague social contract. Rather, they manifest a hitherto wisdom and oxygenate the cultural flame; they are a fulcrum that binds the past to the present.

Conservatism has consistently placed value in the family, yet in recent decades a libertine attitude has prevailed. Politicians who operate as nominal conservatives have relegated the family in their list of priorities.

Some conservatives gleefully accept the social contortion that began in the 20th century, but there is little room for content or complacency. The crypto-Marxist thinkers of the New Left (Foucault, Sartre, Adorno etc) deliberately chose to decimate the family because they knew it would subvert society. In Why Liberalism Failed, Patrick Deneen attributes liberalism as the root of our ailments. Influential thinkers in Hobbes, Locke, Mill, and Rousseau promoted an inherently emancipatory ideology that, by seamlessly granting unprecedented agency, was destined to undermine itself. It contractualized relationships and the family was reduced to atomized individuals rather than a cohesive whole. We live in silos wondering where it all went wrong.

Coupled with the ubiquitous moral degradation of our times, it comes as no surprise America’s marriage rate fell by 6% in 2018 alone with only 6.5 new unions for every 1000 individuals. In Canada, it’s just as bad. The country recorded 2.6 million divorced individuals in 2019 and America’s divorce rate is incrementally shy of 40%. Parents are left oscillating between strenuous work and childcare and children are being raised by social media in a morally bereft era. In lieu of Church, traditional communities, and the intermediaries which compose civil society, we are taught to embrace radical individualistic maxims as normalcy and engage in an unceasing cycle of mass consumption to achieve self fulfillment.

Since its inception, the conservative tradition has consistently maintained the family unit’s primacy in society. Louis de Bonald, a vehement enemy of the French Revolution, maintained the Aristo-Thomist tradition regarding the family. In the Politics, Aristotle conspicuously addresses the family as the wellspring of the polity. Therefore, all political communities are designed to function in an explicitly familial mold and their health is contingent on the wellbeing of individual families. Primarily tasked with inculcating virtue, families act as a medium of transmitting culture, tradition, and faith. Humanity’s gregarious nature inclines us to family and community building. De Bonald reiterates Aristotle in his book On Divorce by inferring the polity’s stability would be subverted and chaos would overtake all previous order if the family dissolves. Just as divorce distorts the family, a miniature society for Bonald, the erosion of family is harmful to political communities. Bonald enjoins his audience to consider the state as being responsible for ensuring the family unit is preserved because it reciprocally induces society’s common-good.

It wasn’t just Bonald who affirmed the family’s irreplaceable role in society. In his infamous study on American democracy, Alexis de Tocqueville espoused similar speculations. Families in New England acted as mediums to mitigate individualism and the instability it renders. Regulating self-interest allowed for democracy to flourish because it substitutes selfishness with a concern for others in the community. Within the family, a clear dynamic existed wherein each respective member had a delineated role. Whereas fathers are concerned with material welfare, mothers are responsible for implanting morality onto children in the hopes of molding them into admirable community members. Uncoincidientally, Nicholas Noloboff indicts the family as America’s “first saviour” and integral to the sustainability of a liberal democratic regime.

When describing justice, Josef Pieper discusses the family’s importance to the foundation of the political community. Influenced by Aristotle’s Politics, Pieper explicitly suggests the state and communities coexist to promote the common good. In sum, families, along with Church, work simultaneously to the state in the promotion of the common good.

Fusionism has failed. Tipid Conservatives can continue to shy away from intellectual tradition but they will be bystanders, if not participants, in the tarnishing of society and culture. A battle for the soul of conservatism is underway. The only solution is to recuperate the tenets of our philosophical history. If not, what are we conserving?

EXCELLENT synopsis , Anthony!